| Still, none of the team’s

regular fabrication team wanted anything to do with the project. Only John Ohlsen, a young mechanic from New Zealand, was interested. John was a

temporary hire and had yet to be accepted into the tightly knit Shelby

organization. They were relieved that Ohlsen could be assigned to the

project leaving them free to continue work on the team’s other racing cars.

So, in the beginning Brock, Miles and Ohlsen were the only ones involved in

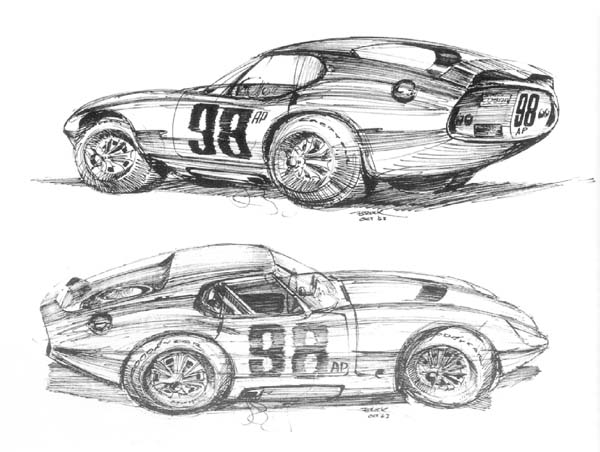

the construction of the first coupe. The design objectives were to wrap the skin tightly about the existing

mechanicals to reduce frontal area, make it sleek to slice through the wind,

and most importantly meet the FIA regulations for details such as windows,

windshield, spare tire, and the like. Pete’s personal challenge was to make

it aesthetically pleasing, a difficult task, as no one in the shop had ever

seen anything like what Brock had proposed and were rather unwilling to

change their minds.

The biggest departure from conventional design came in the rear of the

car. Theoretically the most efficient aerodynamic design would be to bring

the rear of the body to a gradual point, much like an aircraft fuselage. But

that would result in a car that was far too long to be practical. The

prevailing practice was to use far sharper closure angles to bring the

body’s rear section down almost to a point. These sharp angles caused flow

separation and high drag.

While working at GM Peter had discovered an interesting technical paper,

written in the late 1930’s. It pertained to automotive aerodynamic research

attributed to the German aerodynamicist, Dr. Wunibald Kamm. This obscure

treatise suggested another approach to reducing drag. In simple terms,

Kamm’s technicians recommended the use of shallow closure angles to keep air

flowing along the rear body’s surface, and then sharply truncate the form

where practical. The airflow would form a “virtual tail” behind the

truncated body and provide almost the same low drag as a long tapered body.

Plywood bucks, built on an existing Cobra roadster chassis by Brock and

Ohlsen, were taken to Cal Metal Shaping in downtown Los Angeles for

construction of the large hand formed aluminum panels from which the body

would be constructed.

The believers were few and the skeptics abounded. Vindication came on

test day, February 1, 1964, at the Riverside track near Los Angeles. On its

first time out, the bare metal coupe driven by Ken Miles shattered the

team’s previous lap record by three and a half seconds. Aerodynamics, as it

turned out, were incredibly important. This car would be a winner.

The coupe’s competition debut came some three weeks thereafter at the

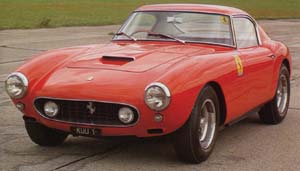

2000 kilometers of Daytona. In number of entries, the new Ferrari GTO

dominated the field, but the sole coupe ran off and left them all. At about

the two-thirds point the coupe was 5 laps in the lead, when a disastrous pit

fire took it out of contention. It had, nevertheless, shown the world that

there was a new international player in the game and it was really quick,

quick enough to embarrass Ferrari’s latest and best offering. After Daytona,

the press began to call it the Daytona Coupe and the name stuck. The Daytona

Coupe faired better at Sebring in March, taking its first win in the GT

class.

The competition then moved to Europe. By then Ford had discretely agreed

to back Shelby’s bid to win the World’s GT Championship. The plywood body

buck was sent to Carrozzeria Gran Sport in Modena, Italy (Ferrari’s back

yard) where the other five coupes were built. The first of the Italian

coupes, CSX 2299, was built before Peter arrived to supervise. It was

modified by the Italian craftsmen, who believed they were “improving” on

Californian’s design. They, like the members of the Shelby team, had never

seen a car with such a radically shaped tail and thought they were

correcting a mistake! They added an additional two inches of headroom in

error. This turned out to be somewhat of a blessing as it allowed Dan

Gurney’s sizeable 6’2” frame to ease into the very snug cockpit that had

originally been designed around a much smaller Ken Miles. The error was

corrected for the remaining coupes.

Both roadsters and coupes were campaigned in Europe during the 1964

season, but as expected the coupes showed their advantage on the longer

courses.

The first European win came at Le Mans in June of 1964 with Bob Bondurant

and Dan Gurney taking first in GT and fourth overall. The two coupes entered

were so fast that they left their GT class competitors in the dust and were

running among the faster prototypes. Boundurant was amazed by the reaction

of the French people. They were captivated by the beautiful body (how

French) and the raucous V8 engine (how American) thundering down the long

Muslanne straight. Everywhere he traveled in Europe after Le Mans, he was

greeted as a hero and a celebrity.

After Le Mans, it was victory after victory. Unable to beat the

all-conquering Daytona Coupes on the track, Ferrari tried to get his mid-engined

250 LM Prototype homologated as a GT car. With only a handful of cars in

existence, the FIA rightly refused. In retaliation, Ferrari then pressured

the Italian organizers of the Monza event to cancel it, depriving the Shelby

team of an almost certain victory and the points that would have carried

them over the top. When it was all over and the dust settled Ferrari won the

World Manufacturer’s Championship in 1964 by the narrowest of margins. But

everyone, including Ferrari, knew that the Daytona Coupe was the class act

of 1964 - an amazing performance in its first year out.

Shortly thereafter Ferrari announced he would not compete with a factory

GT team in 1965. He knew he could not win and channeled all his energy into

the Prototype category. Privateers would carry Ferrari’s GT banner.

Ford and Shelby had turned their attention to the emerging GT-40 program

leaving the Alan Mann racing organization from England to manage the Cobra

effort in Europe for 1965. Under Mann, the dominance by the Daytona Coupes

in the World Manufacturer’s Championship was absolute and complete. The

Daytona Coupes took 1-2, 1-2-3, or 1-2-3-4 in eight of the ten races. The

1965 championship trophy was easily won.

In a final competitive hurrah, the original coupe CSX 2287 was taken to

Bonneville in November 1965 for a series of land speed record runs.

Configured just as it had completed its racing career and with no special

preparation, it set a Class G record at 187 mph and set a total of 23 USAC/FIA

world speed and distance records.

The striking shape of the Daytona Coupe was never tested in a wind tunnel

and its drag coefficient - the measure of aerodynamic efficiency - never

determined. But the Bonneville run gives us the most accurate measure of the

top speed of a particular car and engine under known atmospheric and

altitude conditions. From this data and some rather complex mathematics, I

calculate the drag coefficient to be 0.29. Wow! This is as good as modern

automotive designers have been able to do for the most aerodynamic of modern

cars with computer aided design, wind tunnels, huge budgets, and a strong

directive to reduce drag and improve fuel economy.

The 1964 season began with a single Daytona Coupe, the 1965 season with

four. In all, only six were produced. It is amazing that such a small number

of cars could have such a significant impact on the world of motorsports

competition and on worldwide automotive design.

As beautiful and as successful as they were, the Daytona Coupes were

forgotten at the end of the winning 1965 season. Ford wanted no part of a

design that would threaten its GT-40 on the track, so Dearborn’s contract

with Shelby stipulated that the Daytonas would be abandoned. Ford went on to

great success with the GT 40s.

After the end of the 1965 season, Shelby and Ford had no interest in the

Daytonas, so they were left to languish in Alan Mann’s shop. Mann threatened

to dump them in the North Sea off the coast of the England rather than pay a

huge tax penalty that would be due if the cars remained in England. They had

been brought in under bond with the agreement that they would leave England

after the 1965 season. Somehow the accountants figured out that it would be

cheaper to fly the cars home rather than pay the tax or the cost of their

destruction at sea. So they were returned to Los Angeles where they were

initially advertised for sale for $8,500. Most sold in the $4,000 to $5,000

range and it was several years before all were sold. Since Shelby had moved

on with Ford’s GT-40 program, no attempt was ever made to produce a street

or competition version for sale to the public.

In the intervening years, the world has come to value the Daytona Coupe’s

legendary shape and winning ways. Today, the six Daytona Coupes are each

worth millions of dollars. |